This book (now contracted with Cambridge University Press) explains how the sexes in ageing came to be differentiated according to a binary model in emergent western biomedicine, and how intercultural engagements were crucial in the formation of scientific concepts about ageing disease (morbidity) and longevity (mortality) along sex-differentiated lines between 1700-1910. This was a process that occurred via intercultural entanglements both within multiple European nations and with a variety of non-western cultures. Visions of sex difference in ageing not only meant older women were subject to far greater medicalisation than older men throughout the nineteenth century, but also enabled physicians to reject vitalist premises that equated general health with longevity, resulting in a new separation of morbidity from mortality with reference to the concept of ‘chronic disease’. Gender was not just one aspect of emerging biomedical ideas about ageing but was in fact a constituting consideration as industrialising cultures grappled with the novel problem of increasing populations of people who were living longer but sicker. This was the moment when medicine recognised that urban modernity saw increased lifespans but not ‘healthspans’ (as we now call it). The question of how men and women figured differently in this equation was central to the scientific and medical debates about it.

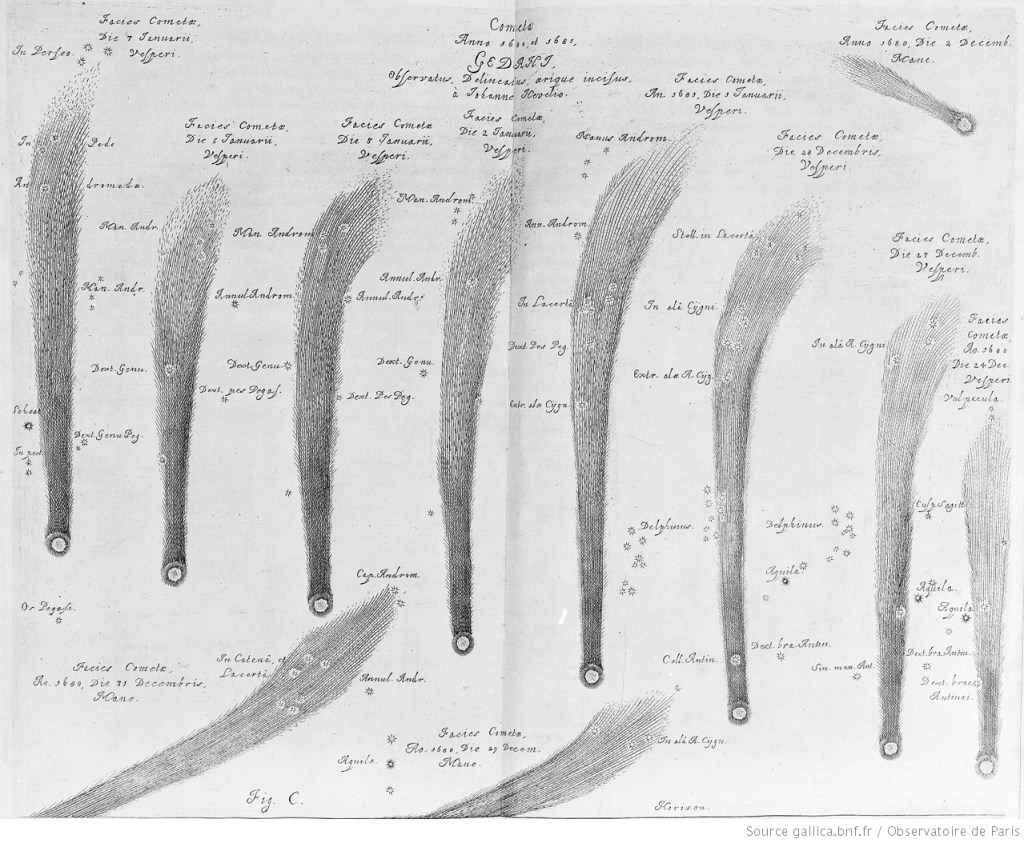

Above: A drawing of the planets influencing climacteric ages in humans, in Johannes Hevelius’ Annus climactericus (1685). While eighteenth-century physicians rejected the astrological explanation of early-modern theories of ageing, they retained the concept of climacteric ages on the septenaries of the human lifespan, giving rise to the notion that women final cessation of menstruation that was commonly observed in the 49th year must represent such a climacteric or crisis, ergo the invention of menopause, and thereafter a bifurcated view of the sexes in ageing.